Inlay by definition is the process of setting pieces of something into a pattern within a larger object. In Indian jewelry terms, it generally means setting small pieces of stone in a pattern within a piece of jewelry. The stones are first cut into small pieces which are then placed within a silver setting to create an unbroken pattern. In that sense, it differs from simply bezel-setting stones on a piece of jewelry (a process by which each stone is within a distinct silver area that is not touching the one next to it.) In a real sense, inlay is like pornography: tough to define but easy to recognize. (And that will be my last reference to pornography in this blog.)

Historically, inlay was the private reserve of the Zuni, who specialized in wonderful stonecutting and stone setting. This was made possible because fine inlay work requires large and heavy grinders and cutters, equipment that fit in with the Zuni's life at the Pueblo but was completely unsuited for the more nomadic Navajo. Carrying a grinding wheel from one seasonal hogan to another would not work for a Navajo artist, but a Zuni smith who stayed in his Pueblo home for the entire year could easily have one in a corner. With the advent of a more "modern" way of life throughout the Southwest, tribal differences in the use of inlay have become blurred or even completely erased, but we will focus on the past for now.

The original type of inlay at Zuni was mosaic inlay on shell. In Mosaic inlay, smaller pieces of (usually) stone are placed edge to edge with no material separating them. Note the small pieces of turquoise on the naja in the above necklace, which are placed directly next to each other on a pitch background. This kind of work dates back to prehistoric times, with many fine examples having been excavated from ruins such as Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon. Turquoise on shell was the most common type of inlay, just like in this necklace, which dates to circa 1910. This is why shell from the Sea of Cortez was one of the most important prehistoric trade items among the peoples of the Southwest, and shell to this day is an important part of many jewelers' bag of tricks.The coming of the reservation and trading post system brought easier access to silver, materials and tools to Zuni, and the art of mosaic inlay became a way for people to support themselves in a "modern" economy. Traders such as the Vanderwagens and C. G. Wallace worked to create a market for this new style of jewelry. The butterfly above dates to 1935-40, and is silver with turquoise, abalone, white shell and jet set in mosaic inlay. Note the pieces of stone and shell are directly touching each other (except for the jet eyes, which are bezel-set.) The overall butterfly design is done with five larger silver channels filled with mosaic inlay, and it is quite likely that the silverwork was done by a Navajo silversmith. Strangely, with very few exceptions, the Zuni were somewhat indifferent silversmiths, perfectly willing to do the inlay on pieces of cardboard which were then given to Navajo smiths to set into silver. Very few Zuni artists distinguished themselves for their work in silver, with most preferring to work entirely in stone and shell. Among the greats of mosaic inlay were Teddy Weahkee, John Gordon Leak (or John Leekity, his real name) and Leo Poblano, with Poblano (died 1959) probably the greatest mosaic inlay artist ever to work in the Southwest. None ever used a hallmark, but each had a distinctive style that sets them apart from their less-talented contemporaries.The other kind of inlay used at Zuni was channel inlay, in which the stones are again set into silver channels, but the channels are much smaller and each one only holds a single stone which does not touch any other stone. The earliest channel inlay likely dates to the mid-1920s, and became extremely common in the 1940s. Often, the demanding silverwork was done by a Navajo smith, who would then hand it off to a Zuni lapidarist to set the stones; the most famous collaborators were Lambert Homer (Zuni) and Roger Skeet Sr. (Navajo). The first channel inlay was what the trade calls "pillow inlay", where the stones stick up very slightly above the top of the silver channels to create a textured look and feel--see the ring above for an example.Over time, it became more common to grind down the stones so that they were flush with the top of the silver, creating a surface smooth to the touch. Note the very refined look of the ring above, with its smooth surface and evenly cut stones. The Zuni artists most proficient in channel inlay were Frank Dishta and Frank Vacit--Vacit used a fleur-de-lis hallmark on later pieces, which Dishta's signature style of small circular stones ground flush is instantly recognizeable.Frank Dishta earrings, showing his style of channel inlay.A way to judge the quality of channel inlay is to look at the amount of "fill" used to fit the stones into the channels. In the photo above, you can see the top left triangular stone, which has uneven edges and grey stuff surrounding it to make it match the shape of the silver channel. That grey material is "fill", and the less fill needed to make the stones fit, the better. If you go back to the green and black ring above, you can see that the silver edges are quite even, and very little fill was needed--a very fine job by a talented channel inlay artist.

For more information on the old-time Zuni artists who made this wonderful work, a great place to start is BLUE GEM WHITE METAL by Deb Slaney. We have a few copies for sale for $20 plus shipping, and it is a small but powerful book that we recommend everyone have in their library. The pieces illustrated here are all shown on our website, and are all available for purchase.

Thursday, April 30, 2020

Thursday, April 23, 2020

Loloma things and Loloma rings

No other American Indian artist has ever reached the heights of popularity achieved by Charles Loloma (1921-1991), the Hopi jeweler, potter and painter whose work, especially his jewelry, has become synonymous with creativity and quality. He took American Indian jewelry to places it had never been, with his designs, his materials and, honestly, his marketing. He was the first public superstar of Indian art, and time has hardly dimmed his reknown; his pieces are just as collectible today as they were when he was alive.

One of the wonderful things about his work is that there is no "typical" Loloma piece. There are designs he made multiple times, such as his "height" and "kachina" bracelets, but there are many other pieces that do not follow those designs at all. A "typical" Loloma piece is a piece done with top-quality materials, expert technique and very pleasing design, no matter the form. And we now have three rings that show some of the stages of his development as an artist, each markedly different from the others but all identifiable as his work by the quality and creativity involved. (Anything said to be "in the book" comes from Marti Struever's comprehensive and highly recommended 2005 book LOLOMA.)

The first ring is the earliest of the three, made during a somewhat experimental time when Loloma was becoming comfortable with the use of lost-wax casting in gold, right around 1968-70. He did this "branch" design with both cultured and freshwater pearls, in both silver and gold, though this is the most elaborate gold example of this type we have seen.Though he did not continue to produce this type of ring in any quantity, the lessons he learned from doing such an elaborate lost-wax casting stayed with him for the rest of his career. In fact, a ring made in 1985 (book, page 169) is not at all dissimilar, though the gold casting is simpler.By the mid-1970s, Loloma had clearly made a conscious decision to only use the best materials available. Not to say that his early pieces were trash, but around this time the quality of his turquoise goes up markedly. Here is a marvelous example of that, a tufa-cast silver ring with a gold bezel and a wonderful piece of high-quality Bisbee turquoise. It is likely to have been made between 1975 and 1980, probably more towards the earlier date.One fascinating thing about this ring is the reinforced silver area at the back of the shank. Loloma was very well known for creating specific pieces for specific people, which means that they sometimes would only fit the person for whom they were made. In this case, he actually put an extra piece of silver on the tufa-cast shank, so that the ring could be sized at a future time without destroying the texture of the band. Later pieces with more inlay were tougher to size, as we shall see....And HERE is an unsizeable one, done in 18k gold with fantastic inlay that goes a large part of the way around the shank. This ring is one of the last things Loloma made, and was done in collaboration with his nieces Sherian and Verma. It was purchased from him at Third Mesa in 1986, just before the September 1986 accident that left him unable to create at his previous levels.Note the height inlay in this ring, more commonly seen on his bracelets. In this little masterpiece, he and his nieces worked to make a miniature version of one of his gold bracelets, with the stones reaching different levels. It is very well engineered, and fits beautifully if your finger is that size (7, to be exact.)

From the experimental to the unmistakable, these three rings together tell a good part of the Loloma story. To see complete information on each ring, go to the RINGS section of the website or call us for more details.

One of the wonderful things about his work is that there is no "typical" Loloma piece. There are designs he made multiple times, such as his "height" and "kachina" bracelets, but there are many other pieces that do not follow those designs at all. A "typical" Loloma piece is a piece done with top-quality materials, expert technique and very pleasing design, no matter the form. And we now have three rings that show some of the stages of his development as an artist, each markedly different from the others but all identifiable as his work by the quality and creativity involved. (Anything said to be "in the book" comes from Marti Struever's comprehensive and highly recommended 2005 book LOLOMA.)

The first ring is the earliest of the three, made during a somewhat experimental time when Loloma was becoming comfortable with the use of lost-wax casting in gold, right around 1968-70. He did this "branch" design with both cultured and freshwater pearls, in both silver and gold, though this is the most elaborate gold example of this type we have seen.Though he did not continue to produce this type of ring in any quantity, the lessons he learned from doing such an elaborate lost-wax casting stayed with him for the rest of his career. In fact, a ring made in 1985 (book, page 169) is not at all dissimilar, though the gold casting is simpler.By the mid-1970s, Loloma had clearly made a conscious decision to only use the best materials available. Not to say that his early pieces were trash, but around this time the quality of his turquoise goes up markedly. Here is a marvelous example of that, a tufa-cast silver ring with a gold bezel and a wonderful piece of high-quality Bisbee turquoise. It is likely to have been made between 1975 and 1980, probably more towards the earlier date.One fascinating thing about this ring is the reinforced silver area at the back of the shank. Loloma was very well known for creating specific pieces for specific people, which means that they sometimes would only fit the person for whom they were made. In this case, he actually put an extra piece of silver on the tufa-cast shank, so that the ring could be sized at a future time without destroying the texture of the band. Later pieces with more inlay were tougher to size, as we shall see....And HERE is an unsizeable one, done in 18k gold with fantastic inlay that goes a large part of the way around the shank. This ring is one of the last things Loloma made, and was done in collaboration with his nieces Sherian and Verma. It was purchased from him at Third Mesa in 1986, just before the September 1986 accident that left him unable to create at his previous levels.Note the height inlay in this ring, more commonly seen on his bracelets. In this little masterpiece, he and his nieces worked to make a miniature version of one of his gold bracelets, with the stones reaching different levels. It is very well engineered, and fits beautifully if your finger is that size (7, to be exact.)

From the experimental to the unmistakable, these three rings together tell a good part of the Loloma story. To see complete information on each ring, go to the RINGS section of the website or call us for more details.

Thursday, April 16, 2020

Four worlds in one--Jesse Monongye in four chapters

For those of you who have read previous blog posts, you will remember that one of the "uniques" I discussed was Jesse Monongye, whose work is as distinctive as it is skillful. For those who are unfamiliar with his work, I recommend the book JESSE MONONGYA: OPAL BEARS AND LAPIS SKIES--the photos are fantastic eye candy, and it explores some interesting parts of his career, including his less than perfect relationship with his father, Preston Monongye. But having the book is not a prerequisite for admiring his jewelry, which incorporates some of the finest inlay work done anywhere into some very interesting forms.

Many great artists have relatively short careers, and Indian silversmiths are no exception. Jesse is definitely an exception to this rule, with his work spanning the years from the 1970s right up to the present day. With such a long career it is only natural that there were different periods to his work, and different styles he adopted during those times. Right now, we are privileged to have four different Jesse pieces, each from a different and distinct period of his career. So, come with us as we visit the career of Jesse Monongye, as told by four pieces in TMT's inventory.

Before we begin, there is one unanswerable question about Jesse--is it spelled Monongye or Monongya? The book spells it Monongya, but Jesse's own website spells it Monongye. Even his own hallmarks are different. We will use the Monongye spelling, because that seems to be what he is using these days. Anyhow, on we go to the jewelry, which is why we are all here.

The first piece is a cast silver belt buckle, which actually has the date 10-22-76 scratched on the back. A very interesting date, since according to the book the first piece Jesse made by himself was in 1977. However, these are some other pieces in the book that are dated 1976, so perhaps this is just sloppy editing. The hallmark on this buckle is four triangles facing each other, which according to Jesse signifies the "four friends"--his brother-in-law at the time and two other friends with whom they were going to start a jewelry manufacturing business. He signed a few pieces from this time with the "four friends" mark, including this buckle. All the jewelry from this time has raised inlay, using smaller pieces of stone (because Jesse could not afford to purchase the larger pieces of turquoise more in vogue at the time.) Note the little piece of coral on the tip of the prong which presages the little creative touches that would come to mark his future work.

Next, a hollowwork silver bracelet with a wonderful piece of Morenci turquoise. Clearly, Jesse was doing better in his jewelry business and could afford better turquoise. But his style was not completely developed--this bracelet is extremely well-made, but it is not instantly recognizable as his work because it is not inlaid. However, this is the most "Navajo" piece we have ever seen from Jesse, who is, after all, Navajo.The signature is engraved, rather than the stamped and/or applied hallmark he would come to use later, but the design of the signature is the same JMONONGYE as on later pieces. A rare, early non-inlay piece, probably from 1977-1980.Aha! Here is the inlay we expect. Some people, including us, call this his "night sky" inlay, for obvious reasons. Absolutely classic work from Jesse, using a number of different types of stones, both traditional (turquoise) and modern (pin shell) These silver earrings probably date to the early 1990s, and have the same JMONONGYE signature as the bracelet, only now it is stamped rather than engraved.And now, we see Jesse go over the top and let his creative juices really flow. This ring has everything--gold, sugilite, turquoise, coral, shell, and even--wait for it--diamonds!Clearly the work of someone who knows who is confident in his abilities and knows that he can afford to incorporate the best materials into his work without worrying that it will go unrecognized (and unsold).There is even a star design on the top of the ring, with three diamonds of various sizes accenting the work. A statement piece, like most of Jesse's work from 1995 on.

In these four pieces, we see most of the major techniques and styles Monongye has used during his career--casting, intricate inlay work, and fabrication in both gold and silver. Truly, a good synopsis of the career of a singular artist.

All four of these pieces are currently for sale on the TMT website. Just go to the Buckles, Rings, Earrings and Bracelets sections for complete details.

Many great artists have relatively short careers, and Indian silversmiths are no exception. Jesse is definitely an exception to this rule, with his work spanning the years from the 1970s right up to the present day. With such a long career it is only natural that there were different periods to his work, and different styles he adopted during those times. Right now, we are privileged to have four different Jesse pieces, each from a different and distinct period of his career. So, come with us as we visit the career of Jesse Monongye, as told by four pieces in TMT's inventory.

Before we begin, there is one unanswerable question about Jesse--is it spelled Monongye or Monongya? The book spells it Monongya, but Jesse's own website spells it Monongye. Even his own hallmarks are different. We will use the Monongye spelling, because that seems to be what he is using these days. Anyhow, on we go to the jewelry, which is why we are all here.

The first piece is a cast silver belt buckle, which actually has the date 10-22-76 scratched on the back. A very interesting date, since according to the book the first piece Jesse made by himself was in 1977. However, these are some other pieces in the book that are dated 1976, so perhaps this is just sloppy editing. The hallmark on this buckle is four triangles facing each other, which according to Jesse signifies the "four friends"--his brother-in-law at the time and two other friends with whom they were going to start a jewelry manufacturing business. He signed a few pieces from this time with the "four friends" mark, including this buckle. All the jewelry from this time has raised inlay, using smaller pieces of stone (because Jesse could not afford to purchase the larger pieces of turquoise more in vogue at the time.) Note the little piece of coral on the tip of the prong which presages the little creative touches that would come to mark his future work.

Next, a hollowwork silver bracelet with a wonderful piece of Morenci turquoise. Clearly, Jesse was doing better in his jewelry business and could afford better turquoise. But his style was not completely developed--this bracelet is extremely well-made, but it is not instantly recognizable as his work because it is not inlaid. However, this is the most "Navajo" piece we have ever seen from Jesse, who is, after all, Navajo.The signature is engraved, rather than the stamped and/or applied hallmark he would come to use later, but the design of the signature is the same JMONONGYE as on later pieces. A rare, early non-inlay piece, probably from 1977-1980.Aha! Here is the inlay we expect. Some people, including us, call this his "night sky" inlay, for obvious reasons. Absolutely classic work from Jesse, using a number of different types of stones, both traditional (turquoise) and modern (pin shell) These silver earrings probably date to the early 1990s, and have the same JMONONGYE signature as the bracelet, only now it is stamped rather than engraved.And now, we see Jesse go over the top and let his creative juices really flow. This ring has everything--gold, sugilite, turquoise, coral, shell, and even--wait for it--diamonds!Clearly the work of someone who knows who is confident in his abilities and knows that he can afford to incorporate the best materials into his work without worrying that it will go unrecognized (and unsold).There is even a star design on the top of the ring, with three diamonds of various sizes accenting the work. A statement piece, like most of Jesse's work from 1995 on.

In these four pieces, we see most of the major techniques and styles Monongye has used during his career--casting, intricate inlay work, and fabrication in both gold and silver. Truly, a good synopsis of the career of a singular artist.

All four of these pieces are currently for sale on the TMT website. Just go to the Buckles, Rings, Earrings and Bracelets sections for complete details.

Monday, April 13, 2020

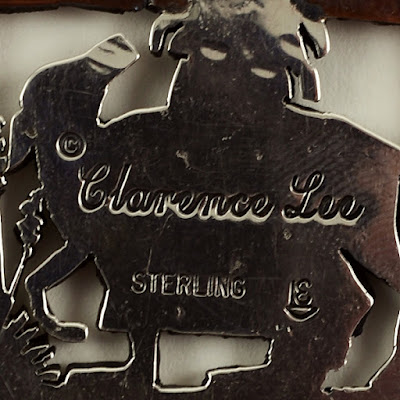

Humor on the Rez--a Pendant by Clarence Lee

When you think of Southwest Indian jewelry and silverwork, many words come to mind, but "humor" is usually not one of them. There is not much funny about the long years of practice it takes to become a skilled silversmith, nor the long hours of filing, stamping and polishing it takes to create a work of art. Great turquoise may make someone gasp, but it rarely makes them laugh. Yet the Navajo are known for having a highly developed sense of humor, which comes out in some of their pictorial weavings. So, why not in silversmithing, which remained a very serious art form until the arrival of one Clarence Lee around 1977.

Lee had always had a talent for drawing, which was not a skill that dovetailed well with silversmithing. But one day he shaped a piece of silver into a form resembling a dog, and from that humble beginning he expanded into scenes of reservation life from when he was young. Before his death in 2011, he had become the originator of the storyteller style of Navajo jewelry, where each piece is a vignette of Navajo life. Which brings us to the pendant in question:

In this pendant, a Navajo woman in traditional blouse and skirt is walking through a landscape that included the sandstone mitten buttes of Monument Valley (which, for added effect, are rendered in copper to mimic the buttes' red color.) Note the moccasins with a large silver button on the ankle, the pleats in the skirt, and the silver buttons lining the arm and shoulder of the woman. There are silver clouds in the sky, and even a sun done in a Zuni inlaid sunface (it is quite likely that Lee purchased these Zuni sunfaces, which often show up in his work, from Zuni artisans rather than making them himself.) Right down to the flowering yucca plant, it is as Navajo a scene as you can imagine.

The humor comes in when you see that the woman is not alone in the scene. By her side is a wooly sheep with its head turned up towards the woman. And in the woman's arms is a little lamb, clearly belonging to the mother sheep. With careful looking, you can see that the mother sheep has a worried look on her face, as if she in wondering what this woman is going to do with her little lamb. The lamb, on the other hand, does not seem to have a care in the world, and is enjoying the ride. After all, why walk when you can ride?

Lee was known for incorporating funny animals into his scenes of reservation life--any pickup truck would have dogs running alongside or sitting in the back enjoying the ride, and cats would often gather by the Hogan to cause trouble while the women did their weaving. There is always something funny about the animals, because Lee said that his memories were happy ones. As a result, the worried mother sheep and the carefree little lamb make us happy as well.

This pendant is SOLD.

Lee had always had a talent for drawing, which was not a skill that dovetailed well with silversmithing. But one day he shaped a piece of silver into a form resembling a dog, and from that humble beginning he expanded into scenes of reservation life from when he was young. Before his death in 2011, he had become the originator of the storyteller style of Navajo jewelry, where each piece is a vignette of Navajo life. Which brings us to the pendant in question:

In this pendant, a Navajo woman in traditional blouse and skirt is walking through a landscape that included the sandstone mitten buttes of Monument Valley (which, for added effect, are rendered in copper to mimic the buttes' red color.) Note the moccasins with a large silver button on the ankle, the pleats in the skirt, and the silver buttons lining the arm and shoulder of the woman. There are silver clouds in the sky, and even a sun done in a Zuni inlaid sunface (it is quite likely that Lee purchased these Zuni sunfaces, which often show up in his work, from Zuni artisans rather than making them himself.) Right down to the flowering yucca plant, it is as Navajo a scene as you can imagine.

The humor comes in when you see that the woman is not alone in the scene. By her side is a wooly sheep with its head turned up towards the woman. And in the woman's arms is a little lamb, clearly belonging to the mother sheep. With careful looking, you can see that the mother sheep has a worried look on her face, as if she in wondering what this woman is going to do with her little lamb. The lamb, on the other hand, does not seem to have a care in the world, and is enjoying the ride. After all, why walk when you can ride?

Lee was known for incorporating funny animals into his scenes of reservation life--any pickup truck would have dogs running alongside or sitting in the back enjoying the ride, and cats would often gather by the Hogan to cause trouble while the women did their weaving. There is always something funny about the animals, because Lee said that his memories were happy ones. As a result, the worried mother sheep and the carefree little lamb make us happy as well.

This pendant is SOLD.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)