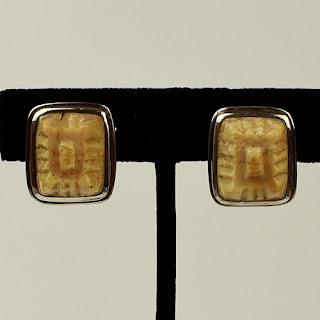

Recently, Diana and I were looking at a pair of earrings with an eye towards a possible purchase. It was a very nice pair, an early Zuni pair with wonderful work and very nice old turquoise. In fact, it looked a lot like this:

As a disclaimer, please remember that these choices are all entirely personal, and others may not agree. Some people will only purchase items that are completely original, not repaired or modified in any way. (These people tend to have very small collections.) But as someone who has been through my share of rodeos, I can speak from long years of experience and say what the market in general is willing to accept.

In the case of this pair of earrings, a distinction needs to be made between the body of the earring and the findings. The earring itself starts at the loop soldered on to the top, and everything below is integral to the original piece. However, the finding to which the loop is attached, in this case a button and post, is not only not original but almost certainly not made by the original artist. This is not at all unusual, in both contemporary and historic pieces--findings, such as earring posts or clips, bolo clips and pin backs, are often commercially made and added to the body of the piece as needed. So, while this pair of earrings would have been enhanced if the original hooks were still functional, it is not much of a problem that the findings are not original.

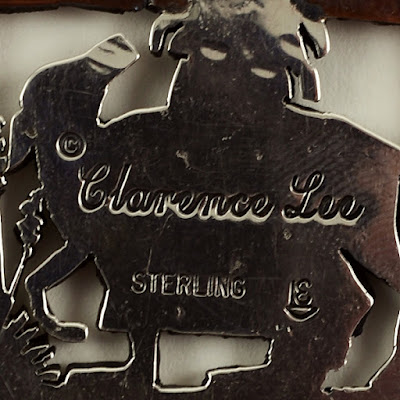

But what if the repair was a conversion, instead of a simple fix? What if the pair had been split up and each one converted to a pendant? That is a different story, and would be a problem for most collectors. Strangely, though, the same does not always apply to pins and bolos, which have a long history of being converted. With those, the question is where the original artist stopped--did he or she simply make something and then hand it over to a trader to make into whatever they thought would sell, which was the case with many old Zuni pieces? If the artist was a noted inlayer, like Leo Poblano, he would almost never do the silverwork; he did not have the final say in what form his work would take, so a conversion does not go counter to his original wishes. But if the work was that of a Navajo silversmith like Kenneth Begay, who would have attached his own finding, it should be kept the way it was originally made. (This does not apply when considering clip earrings, which can be converted to posts or vice versa without any problem, as long as the conversion does not harm any hallmark.)

What about resizing rings? That is probably the most common type of modification we see in the business, but is it a problem? The simple answer is no, with a caveat. The resizing should be well-done, and should not harm any markings on the inside. It also should not disrupt any pattern on the outside, which is where the problem arises on many contemporary rings.

Repairs are the same as resizing--if it is well-done and does not affect the integrity of a piece from either a structural or design standpoint, then it is okay. Granted an unrepaired piece in perfect condition is always preferable, but many of these items are a century old and have seen 100 years of wear. It is unreasonable to expect perfection. Instead, we should expect beauty.