In our last post, we discussed the origins of stone inlay in the Indian Southwest, with a special emphasis on the work done at Zuni Pueblo. Today, we will look at what has happened to the art of inlay since the 1960s, with special attention paid to the best inlay artists of the present day.

The 1960s and 1970s were, to put it bluntly, bad decades for the art of inlay. Not only did the 1960s see the death of many of the great inlay artists at Zuni (Poblano in 1959 and Weahkee in 1966 are two notable ones) but the increasing popularity of Indian jewelry led to the inevitable flood of foreign fakes on to the market. Even the genuine articles being produced at Zuni were generally unimaginative copies of earlier styles and forms. Two notable exceptions were the husband and wife teams of Nancy and Dennis Edaakie and Virgil and Shirley Benn, whose work was carefully and creatively done.Dennis EdaakieVirgil and Shirley Benn

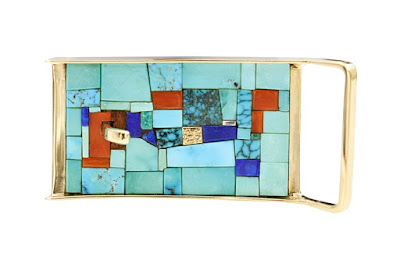

The return to high quality work happened not at Zuni, but at Hopi with Loloma and In Joe Tanner's Gallup store with his stable of (mostly) Navajo artists. The work they all did was very unlike that done at Zuni, but the quality was generally of the highest quality.An inside inlay belt buckle by Charles Loloma

Loloma's work was unlike anything ever seen before in Indian country, and his "cornrow", "height" and "inside inlay" inlay styles quickly became a part of many artists' repertoire. Having already discussed Loloma at length in other posts, we will not spend more time on him here, apart from acknowledging how hugely he influenced everyone in the Southwest.

Much of the truly high-quality inlay work done at the Tanner store was focused around the work of one man--Preston Monongye. Preston was not the best inlay artist, but his cast silver forms were a great frame for the work of other people, several of whom are counted among the greatest lapidarists of their time. Tanner would take silver blanks designed and cast by Preston and give them to people like Jimmie Harrison, Lee Yazzie and Jesse Monongye, who would work their lapidary magic.Preston Monongye silver bracelet with inlay by Lee YazziePreston Monongye silver bracelet with inlay by Jimmie HarrisonPreston Monongye cast silver bracelet, with the inlay done by himself. Monongye would often take longer pieces of stone and score them, to give the illusion of many smaller inlaid pieces.

Harrison, Yazzie and Jesse Monongye all went on to have great careers of their own, of course, and their work is an inspiration to several generations of inlay artists. Two of the most notable are Lee's younger brother Raymond Yazzie and Carl Clark, a Navajo artist who works with his wife Irene to create incredible micromosaic masterpieces.A silver bracelet by Raymond YazzieA silver ring by Carl and Irene Clark

It is ironic that the finest and most talented inlay artists working today are Navajo, considering that historically, inlay was a Zuni art form. An explanation can be found in the fact that Indian jewelry today is a professional occupation, and Navajo jewelers are not the nomadic sheepherders of old--they have houses and a modern lifestyle, and a place to keep the large and heavy machinery needed to do high-quality lapidary work. The work of Loloma and the Tanner shop artists helped to break down the long-held preconceptions about what "Navajo" or "Hopi" jewelry should look like, and replaced them with the idea that each artists can and should have his or her own style. We live in the era of the individual artist, which for knowledgeable collectors is a great place to be. That is not to say that there are not great Zuni inlay artists--the work of Colin Coonsis leaps to mind--but inlay has gone from a Zuni province to an art form that can be owned by anyone, regardless of tribal affiliation.

Friday, May 15, 2020

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

The Preston/Harrison bracelet is wild. Although totally different in style, it reminds me in its use of exuberant color of the 'tutti frutti' bracelets designed by Cartier.

ReplyDelete